Siberian gulags, the KGB building and radio observatories used for espionage.

Text and images by Travel Purist

Not on the usual tourist circuit, Latvia is a country that takes you by surprise. Few know that its sub-zero winter temperatures are offset by beautiful beaches and while the capital, Riga, is sure to blow your mind with its pretty Art Nouveau architecture and streetside buildings that exude fine art, you will find that Latvia’s most interesting historical sights are also its darkest.

Once part of the German, Swedish and Russian empires as well as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Latvia was forcibly occupied by Soviet Russia in 1940 and won its independence only in 1991. The Soviet era was possibly the darkest period in the country’s history and the Occupation Museum (Strelnieku Square, opposite Akmens Bridge, Riga) documents much of the history and horror of the period including a reconstruction of the Siberian gulags that much of the population was deported to on flimsy grounds. Just outside the museum is the Riflemen Monument – a Soviet era tribute to Lenin’s bodyguards – while a short distance from here is the Freedom Monument that honours soldiers killed during the Latvian War of Independence. But the building that’s sure to sober your holiday mood is the KGB Building, now a museum.

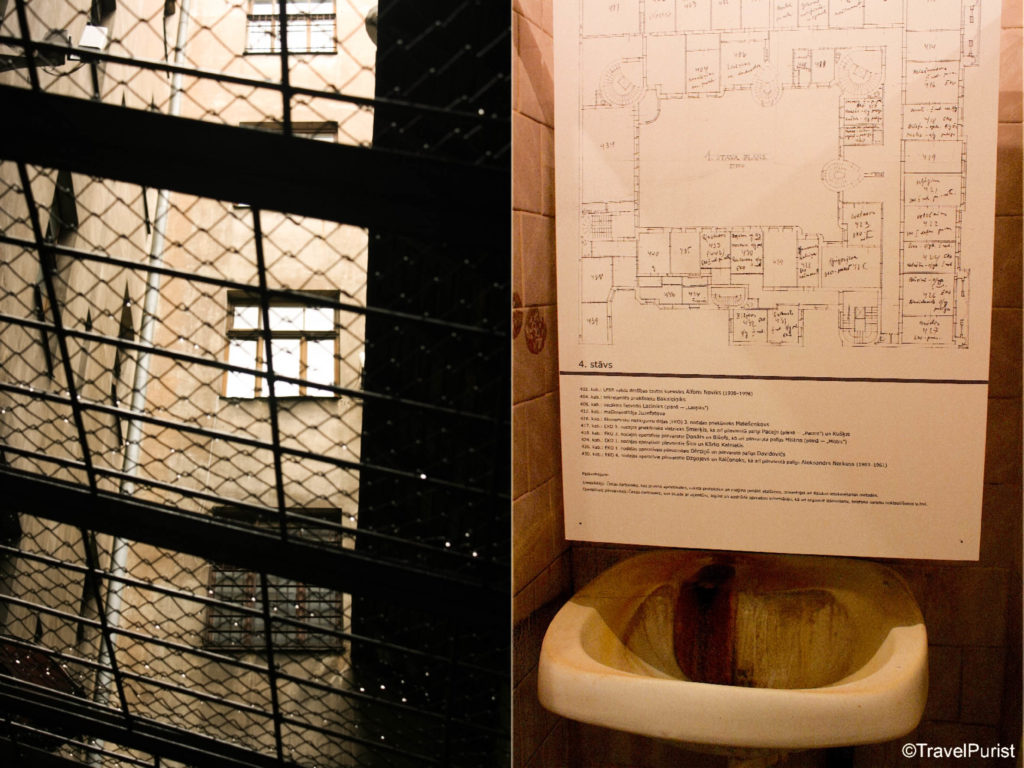

Inside the Occupation Museum. Left: Reconstruction of a Siberian Gulag.

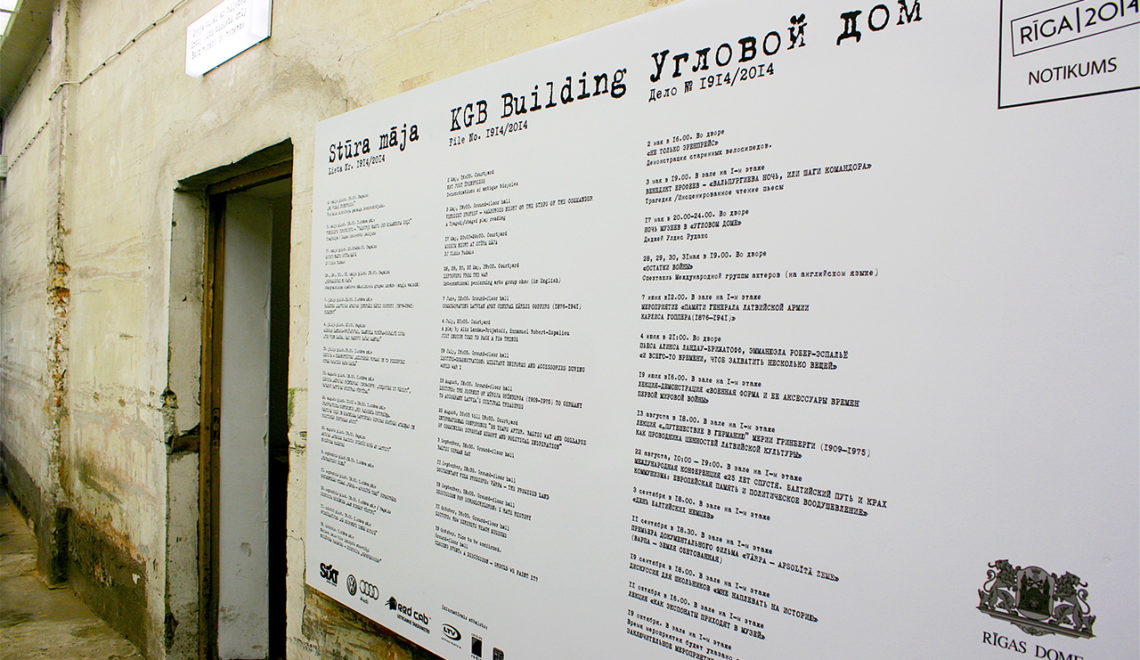

Known locally as the ‘Corner Building’, the KGB Building (Brivibas iela 61) was Riga’s original house of horrors. The headquarters of the ‘Cheka’ or the Soviet Secret Service, its beautiful Art Nouveau façade is deceptive; it hides the ugliest reality of Latvia’s Communist regime. Guided tours are conducted in English, Latvian, German and Russian, and visitors are forbidden entry on their own for fear that they might get lost in the maze of rooms and torture chambers.

“…the Soviet Union always appeared to be the world’s most active fighter for peace but never for a moment abandoned the idea of a global proletarian revolution or the struggle against imperialism, the result of which was the Cold War and armed conflict in just about every continent after World War II. Prisoners have also remembered the interrogators’ characteristic manner of questioning, when apparent kindness and helpfulness were followed by a brutal blow and torture, if the hoped-for objective was not achieved with ‘humane’ methods,” says the detailed introduction to the building, in a brochure provided by the Riga 2014 Foundation.

The interior is proof enough – art exhibitions and film screenings bring alive the terror of the repressive era, and the guide leads us through the detention cells, interrogation rooms and narrow passageways mockingly nicknamed ‘King’s Street’ (for the slightly better condition of its inmates) and ‘Rose Street’ (occupied by female prisoners) by Secret Service agents. A dark cell with a tiny window that lets in barely a sliver of light is transformed by the flick of a switch and we are told, as we squint in the blinding glare of bright lights, that these lights were left on all night, which together with night-long interrogation, ensured that the prisoners were left in a state of more-or-less permanent sleeplessness. Once inside this house of terror, politicians, artists, writers and others usually disappeared without a trace.

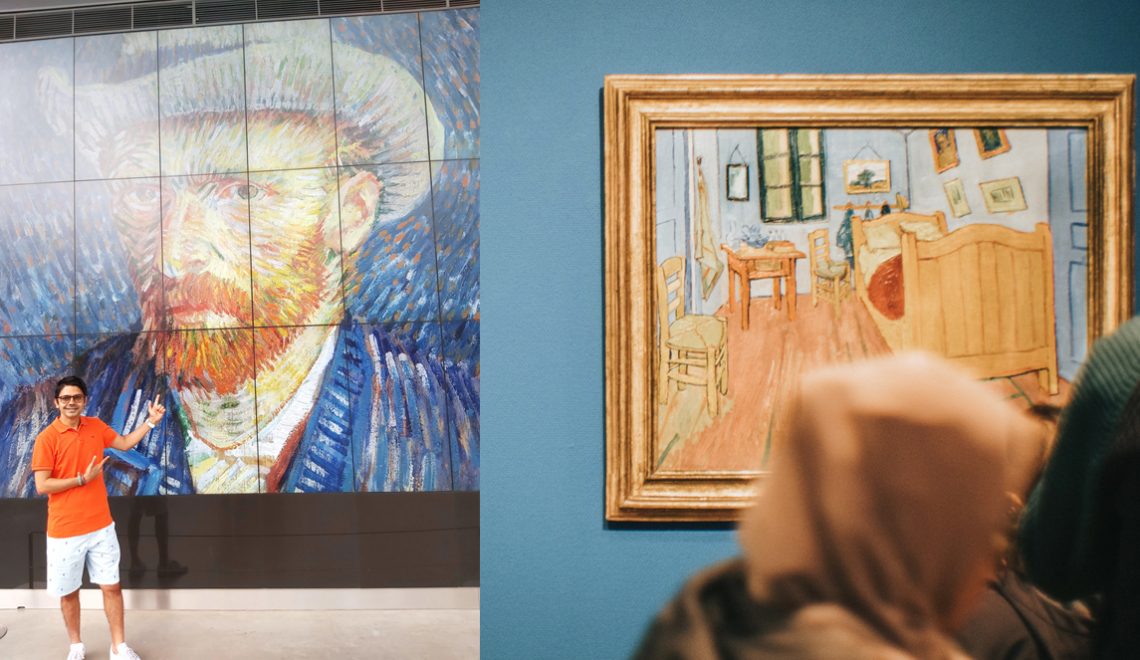

Inside the KGB Building known as the ‘Corner House’.

Onward to Ventspils, the terrain gets more ‘East Bloc’ and Riga seems almost West European in comparison. Soviet era buildings continue to be used as residences by locals while some have turned into hospitals and university accommodation. A working class Soviet canteen near the beach continues to serve traditional Latvian and Russian meals at Soviet era rates and a little old lady at the Central Market sets up her stall of coins, badges, medals, antiquarian books and other memorabilia from Soviet times.

Beyond Ventspils, past the beautiful coast of Staldzene and not far from the lighthouse at Ovisi, are structures that seem to have emerged from the pages of a Tintin comic book. Hidden amid vast forests of oak and pine trees is chilling evidence of Soviet espionage – radio observatories that once picked up local telephone conversations. The big observatory at Irbenes is closed to visitors now, having been bought over by a German company for research in astronomy. The smaller one allows ticketed entry and you can climb all the way up to the top, should you have the stomach for it.

The radio observatory at Irbenes.

From outside, the observatories look like giant rusty satellite receptors. From the inside, they look like something from Dr Zhivago-meets-James Bond. A mass of vintage (then state-of-the-art) equipment punctuated with hazard warnings in Russian, the paint peeling from walls that could tell a million stories, the structures seem to let you in on a secret hidden from the rest of the world. Close to the observatories are deserted, dilapidated residences and schools built for the Soviet spies and their families – structures that were hastily abandoned after Latvia won its independence. Locals would discover the observatories only in 1991, the area (a 100 km radius around the observatories) having been out-of-bounds for unsuspecting locals who were oblivious of their existence.

Latvia shares its border with Western Russia and for many a local Latvian who’s lived through Soviet times, the crises in Ukraine and Crimea have been enough cause for sleepless nights. “Never again,” said a Ventspils resident. “I have spent a serious amount of time planning our escape in case of sudden occupation by Russia.”